here are our foolish takes, hot and cold. based largely on reality.

('24)

.

you can find more arguments in the physical editions of the fool or in the archive or in the sagas section of the website. its not that hard lol

Documentary poetics is defined as art in which a primary document constitutes the surface of the piece, but is manipulated in order to reflect or communicate an external experience. The power of documentary poetics is built in part on the emotional weight of the primary documents these pieces prioritize. This is attributable to many theories of art, among them affect theory, as well as Roland Barthes’ definition of the punctum.

In light of affect theory and its practical applications in collage and assemblage, as well as the framework put forth by Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida (which is arguably an instance of documentary poetics itself), the vast majority of zines can be understood as examples of documentary poetics, although their existence as a medium precedes its definition. Through this recapitulated understanding of zines and their formal influences, a model of research and resulting writing that is led by the erotic, in the sense as it was defined by Audre Lorde, begins to reveal itself.

Roland Barthes was not a photographer. He worked mainly as a literary critic and theorist, work that informed his piece of writing on criticizing photography, Camera Lucida. This text, then, studies photography from a lens only of viewership and not of embodied practitionership. Barthes examines his own method of viewing photography, attempting to distinguish that which makes a photo pleasurable from that which might make it technically good in the way a photographer might define it. Two phrases are key to his analysis; the punctum, that in the photograph which pricks, leaves the viewer wounded, and sticks in their sight after the photo leaves it, and the studium, the cultural context related to or implied in the image, which informs our understanding of it.

Barthes includes a wide variety of images in Camera Lucida, all of which he picks apart in search of a punctum and studium. In this way, he simultaneously imparts an experience of them and allows the reader to have their own experience. He keeps the primary documents, the photos, on the surface, but influences their impact by instructing the reader to examine the distinct aspects of their reaction to it, just as contemporary practitioners of documentary poetics do by presenting external experiences through the presentation and manipulation of historical texts and pictures.

Camera Lucida, then, is a kind of forerunner of the genre of documentary poetics, an early example, even if it is perhaps only visibly so in the light of its descendants. There is, of course, a perfectly viable counterargument that Camera Lucida is not at all documentary poetics, as it speaks only to Barthes’ experience and not an external one, or because its primary documents are not manipulated by any means other than juxtaposition with a commentary on it. This dismissal of juxtaposition as a valid means of manipulation, however, is contradicted many times over by the revolutionary practices of assemblage, montage, and collage, which are of course underpinned by the realities of affect theory.

The less tenuous connection between Barthes’ theory and documentary poetics lies in Camera Lucida’s implied argument for the strength lent by the incorporation of primary sources in media such as documentary poetics. By leaving primary sources visible in the final piece, artists allow the punctums of the original documents to stand, whatever each punctum may be for each audience member. Information is included that could never be translated out of the primary source into the artist’s voice, because that which is powerful and compelling in photos or other documents is often unnameable, indescribable. As Barthes says,

If the goal of documentary poetics is to wrench the heart, to prick and disturb, then the preservation of sources is among the most direct mechanisms to achieve it, according to Barthes, as it is only by leaving the unnameable (and thus untranslatable) intact that it can be communicated in its full force to the viewer.

My experience of research (and writing about it) has a lot to do with the way the punctum of the documents I come across plays upon me. Particularly strong are my memories of researching the role of video and the activist-artists who used it in the ACTUP movement — While watching the videos that came out of that scene, I felt a strong sense of affinity with those on screen, and a longing to be among them. Perhaps this is why Barthes’ description of his reaction to a photograph of an old house resonates so strongly with me. He writes,

(Above is the photo in question). This final line especially, “This longing to inhabit [...] deriving from a kind of second sight which seems to bear me forward to a utopian time, or to carry me back to somewhere in myself,” is as reflective of Barthes’ reaction to this photo of the house as it is of my reactions to videos of queer activism. Because of the punctum (or punctums… I think we should be allowed several in a video) of the footage I was watching, I experienced the primary documents of my research with intense emotion, feeling fully into the pride and community they celebrated, and I wished to exist within them. Although in much of the documentary poetics I have come across the inverse is true, in that the primary documents on the surface of the work generate a deep sense of discomfort and or disapproval in me, it holds the same strength as my experiences of ACTUP videos because of this preservation of the original object and its particular affect. Additionally, the strength of the feeling is the same — a lack of neutrality, a similar level of activation — and that is due to the punctum and the capability to disturb that lies in its ineffability. Whether positive or negative, there is pleasure to be found in this activation. Let us not forget that Barthes’ theory of photography criticism was driven by the pursuit of whatever pleasure is to be found in photos.

This, along with my experiences of joy in the many punctums of my research, begins to form a model of research driven by the erotic. As Audre Lorde defined it in Uses of the Erotic,

This nod to “the chaos of our strongest feelings,” moments of high activation, tie Lorde’s theory of the erotic to Barthes’ understanding of the punctum as an instigator, an object that disturbs. The erotic certainly plays a role in Barthes’ theory of the punctum, and although he doesn’t appear to be working off of Audre Lorde’s definition as of Uses of the Erotic (although it was published two years before Camera Lucida), their understandings seem to align.My professor, the wonderful An Duplan, at this point in my essay commented that I should write a bit on the difference in Lorde and Barthes’ social positions. While Barthes wrote about the punctum and its eroticism in search of articulating a theory of photographic criticism, working as a French, white, male literary critic, Lorde wrote, as a Black lesbian, about the erotic and how it might enable others in her position be empowered by feelings usually discounted by American culture.He writes,

Like Lorde, Barthes relates it to “the absolute excellence of a being, body, and soul together,” similarly to how Lorde defines the erotic as a sense both bodily and emotional that guides the being more fully than other motivations. He also positions the erotic and the pornographic in direct opposition, just as Lorde does in Uses of the Erotic. Of the relation between the erotic and the pornographic, Lorde writes,

Because of this twice-asserted thesis, that pornography and eroticism are mutually exclusive, Barthes’ assertion that “there is no punctum in the pornographic image” takes on an implication that the punctum is inherently erotic — not that it is sexual, but that it is the site of the instigation of “the fullness of the depth of feeling,” as Lorde puts it, that once we have experienced it, “in honor and self-respect we can require no less of ourselves.” The curiosity instigated by the erotic image, the punctum which lies in “a kind of subtle beyond, is in itself an erotic drive, a pursuit of the pleasure which Lorde argues there is an honor-bound obligation to follow once we have experienced it.

This is the erotic curiosity that ideally guides research, the first tastes of which has driven much of my research writing. For instance, my desire to research the socialist women’s unions of the 70s is due in large part to this photograph, which comes from the site of Our Bodies, Ourselves.

For me, the punctum here is the downcast eyes of the woman with the darkened glasses on the right, but what draws me more than that is what is absent from the image, what teases me from its shadows, what there is to be learned, or perhaps that of which knowledge is unattainable, about these women — their motivations, the conditions of their lives, or their roles in the work that I do know they accomplished. My capacity to identify with them as women, feminists, organizers, writers, and zine-makers (of a sort — Our Bodies, Ourselves was a much more polished and professionally produced project than any of my zines, or those which will come under discussion later in this essay) also introduces an erotic draw, as I am guided by my affinity to them.

However, this group of (at least seemingly) solely white women would not prick the same nerve of affinity in everyone. This evinces one advantage of preserving the primary document, to allow for transparency around the artist’s subjectivity, but also the importance of being guided by more than pleasure — allowing one’s work to be led by other emotions of high activation, other prickings, other curiosities about these women, namely whether their efforts were as exclusive to white women as this photo indicates, and if their movement was friendly to women and people of color. This all has more to do with the studium than the punctum, even if it involves similar feelings of activation, as it deals with the surrounding cultural context and politics involved in this photo. Pleasure is not enough to guide full-bodied research, as examining even that which makes one uncomfortable is necessary to ascertain an understanding of the scene in its entirety. However, this discomfort could still be capitulated as an erotic feeling, as it involves a deep, embodied activation.

The same sense of identity and erotic curiosity that has driven my research into ACTUP artist-activists and the socialist women’s unions of the seventies has also drawn me to the products of another scene, the community and culture of zine-making. One of my first exposures to this medium was a gift from my older sibling’s partner, a zine called carotte sauvage: wild carrot seeds as herbal birth control. Its aesthetics play upon conventional zine techniques. Some of its text is written on a typewriter, some of it in a close-set sans serif, and whole pages of it are handwritten, all of it bumping up against or cut up and pasted over Xerox-distorted images of wild carrot flowers and their seeds. Several portions of the text are photocopied straight out of manuals for the identification of herbs or guides to herbal fertility methods. (A punctum — on the inside cover, crooked against the bottom of the page, is written by hand “anti-copyright 2005 (first edition) - copy + distribute!” The “a” of “anti-copyright” looks like an @ symbol, although it may be a quickly scrawled anarchy sign. There’s something in this confusion which could speak to the free, anarchistic flow of knowledge via the internet, but what pricks me here is the shape of the “5” in “2005” — It reminds me of someone familiar’s handwriting, but I can’t remember whose.)

At first glance, this zine obviously does not appear to be an instance of documentary poetics. While many primary sources lie on its surface, photocopied in, they are integrated only into a discussion of their subject matter; no external experience is notable in the text of carotte sauvage. On the other hand, the integration of the source of the knowledge with the author’s writing and acquired understanding mimics the process of reading and learning to communicate the experience of carotte sauvage’s research and writing. The reader is allowed to experience both the information in its primary form, in all its punctuousness (if you will), to react to it as it existed originally, and to understand the artist’s reaction, processing, understanding, and stance on the material — the central effect (or affect, if you’d like) of documentary poetics.

The process of reaction is also visible in how tangible the writing and assembly of the zine is — the zine’s materiality implies the books read, scanned, the passages typed, the time spent pasting and drawing and photocopying and folding. This energy is felt not just in carotte sauvage, but in most collage-heavy zines. In this way, the zine as a form is a materialization of the erotic drive of research. Particularly in the myriad of zines that have come out of many punk and DIY scenes, activation (whether love for peers and punk culture, or rage against The Man) is highly visible in the processes of tearing apart, collaging, and recapitulating through juxtaposition, all of which take place both in the making of and remain on the surface of zines.

Take Beans and Franks Zine, subtitled written for losers by losers: pointless, stapled pages of goo-goo, a zine that is largely about the personal experiences and reflections of the members of what seems to be a punk house in Pensacola, Florida, but is also seemingly intended to serve in part as an informational and instructional source about BMX and punk biking culture. One spread in Issue 9 on Beans and Franks is about getting harassed by cops while being ticketed for riding bikes being towed by a band’s van. The left page is a handwritten narrative, while the right is a photocopy of the ticket itself, as well as another ticket for skateboarding on the sidewalk. By juxtaposing the distinctly personal account with the government record of the event, the spread points out the lack of humanity present in the primary source — There is documentary poeticism at play here — but also preserves the visibility of the artist. The authorial voice is not completely given over. The writer remains extremely and punctuously tangible in the piece.

Because of this, the zine, especially in its existence in the senses, is another site of curiosity and projection, similar to that provided by the erotic photograph discussed by Barthes. Thus, the zine serves not only as an example of documentary poetics because of its system of self-contained presentation and reaction, but because of the visibility of the creator, it also often evokes the same erotic activation which it reflects. Zines’ extreme materiality not only maintains the original punctums of their source texts or photos, but produces innumerable punctums by keeping the process of reaction not just on the surface, but extremely present in the style of the medium.

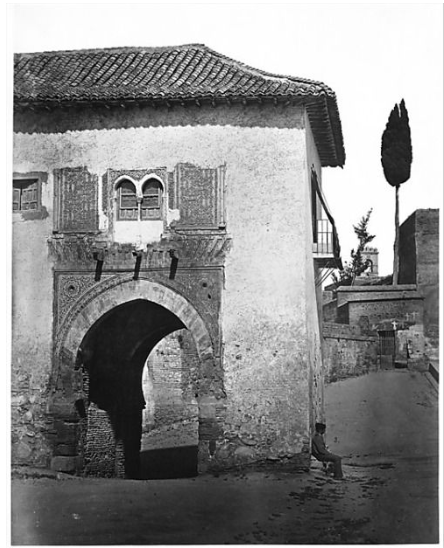

The erotic curiosity that zines inspire is not something only I experience. A few pages from the end of Beans and Franks Issue 9 is a letter from a reader, Joshua, typed on a typewriter and directly photocopied in. He’s written, “I found your publication both enertaining [sic] and upbeat, while retaining a personal realness witch [sic] made me feel close to the writer and in places touched me emotionally.” (The spelling is his own; From his post-script, “I don’t beleve in correct spelling&spell phoneticlly for the most part so dont laugh, correct spelling didn’t even exist (and doesnt in most languages) until websters dictionary was approved by the english as the offical kings english.”) Vertically along the edge of the page, Joshua has written by hand, “are you people really just like me?” The desire to inhabit that Barthes speaks to in Camera Lucida is expressed here. Joshua, it seems presumable, has been pricked by Beans and Franks. “I loved the zene& would love to meet u if your ever in mobile look me up. maybe ill see you in pennsicola. whatever,” he closes his letter, and signs it, “save me, joshua.” This sense of longing smacks of Barthes’ reaction to Charles Clifford’s photograph, “Alhambra,” and my own to photos and videos of feminists and lesbians from forty and fifty years ago. This is an erotic sense, as evidenced by its relationship to the punctum.

Zines, by their preservation, within both primary documents and the authorial voice, of punctums, sites which activate an erotic curiousity as defined by Lorde and Barthes, expand documentary poetics and evince the tenets of affect theory, endowing them with the power of the erotic, even if they really are pointless, stapled pages of goo-goo.